인간광우병(vCJD)의 원인 물질인 프리온 단백질이 신경계에서 핵심적인 역할을 한다는 연구결과가 [네이처] 뉴스에 소개되었습니다.

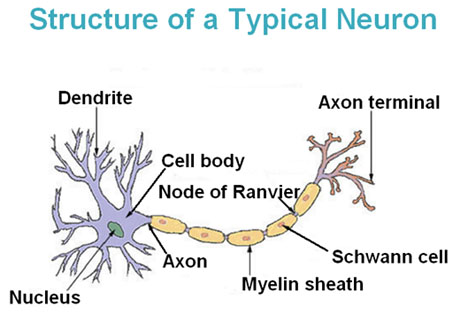

신경과학자들로 구성된 다국적 연구팀은 포유동물에서 프리온 단백질은 신경의 축삭돌기를 둘러싸고 있는 여러 겹의 슈반 세포막층인 수초(髓鞘, myelin sheath)를 유지하는 기능을 한다고 보고했습니다.

Axonal prion protein is required for peripheral myelin maintenance

Juliane Bremer, Frank Baumann, Cinzia Tiberi, Carsten Wessig, Heike Fischer, Petra Schwarz, Andrew D Steele, Klaus V Toyka, Klaus-Armin Nave, Joachim Weis, et al.

Axonal prion protein is required for peripheral myelin maintenance

Juliane Bremer, Frank Baumann, Cinzia Tiberi, Carsten Wessig, Heike Fischer, Petra Schwarz, Andrew D Steele, Klaus V Toyka, Klaus-Armin Nave, Joachim Weis, et al.

출처 : Nature Neuroscience (24 January 2010) doi:10.1038/nn.2483 Article

연구팀의 연구결과는 [네이처 신경과학] 2010년 1월 24일자에 게재되었습니다.

이 기사에는 스위스 출신의 세계적인 프리온 연구의 권위자 아드리아노 아구치 박사의 20년에 걸친 프리온 연구에 대해서 간단하게 소개되어 있기도 합니다.

최근 과학자들은 프리온 단백질이 후각이나 시각과 관련이 있다는 연구결과를 발표한 바 있으며, 프리온 단백질이 알츠하이머병이 발생하지 않도록 보호해주는 기능을 한다는 연구결과 등을 발표하기도 했습니다.

=======================

Healthy prions protect nerves

Alison Abbott

출처 : Nature News (24 January 2010) doi:10.1038/news.2010.29 News

http://www.nature.com/news/2010/100124/full/news.2010.29.html

The proteins that can cause CJD have a vital role in the nervous system.

Prion proteins help to keep nerve cells well insulated.STEVE GSCHMEISSNER / SPL

Prion proteins help to keep nerve cells well insulated.STEVE GSCHMEISSNER / SPLAfter 20 years of research, scientists believe they have finally uncovered the normal function of prion proteins, which can cause deadly illnesses such as Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) if they become incorrectly folded.

An international team of neuroscientists reports that, in mammals, the mysterious proteins help to maintain the myelin sheath that protects the body’s nerves.

“This opens a new door to studying some of the many common neuropathy disorders — which lead to weakness or loss of sensitivity of limbs — where we don’t know the cause,” says prion expert Simon Mead at University College London’s Institute of Neurology.

The authors suspect that their finding also applies to brain neurons. If so, this would have implications for treating deadly CJD and other transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. It could also offer a new way of looking at multiple sclerosis, an incurable disease caused by demyelination of nerves in the brain and spinal cord. The work is published online in Nature Neuroscience today1.

Long search

Several functions have been proposed for prions during the past couple of decades, but none has survived close scrutiny.

“The first mouse with knocked-out prion genes was made back in 1991,” says Adriano Aguzzi at the University Hospital of Zurich in Switzerland, who led the new work. “We leapt on it, and studied it in every way we could think of — but never managed to find any obvious sign that lack of the prion was causing it harm.”

In fact, at first glance, lack of prions seemed like a good thing because it made mice immune to prion infection.

But four years ago, Aguzzi started to think again about a generally overlooked 1999 paper2 by researchers in Japan that suggested the lack of prion protein caused the degeneration and demyelination of nerves outside the brain. He decided to undertake a thorough and systematic analysis of prions’ effects on such peripheral nerves.

Together with his colleagues, he studied four different strains of mice lacking the gene for the prion PrPC. In every mouse they tested, regardless of strain, they found early evidence of myelin damage just six weeks after birth. By the age of two months, the nerves were extensively demyelinated, and the mice had become more sensitive to pain.

“Because there is no myelin damage at birth, we assumed prions are needed to maintain the quality of the myelin sheath, which diminishes throughout life,” says Aguzzi. Accordingly, when the researchers re-introduced prion proteins specifically into nerves, the demyelination did not occur. Curiously, however, only variants of prion proteins susceptible to cleavage by enzymes were effective.

But no variant of prion protein was able to prevent demyelination when introduced specifically into the Schwann cells that surround and support peripheral nerve cells. “This surprised us,” says Aguzzi, “since Schwann cells actually do the job of manufacturing fresh myelin.”

Aguzzi concludes that when nerves’ sheathes are suffering wear and tear, the nerves enzymatically cleave their prion proteins, releasing fragments that travel to Schwann cells, where they signal activation of myelin repair.

Brain effects

He also has a hunch, supported by preliminary data, that prion proteins will turn out to play the same part in supporting myelination in the brain. “So it is going to be interesting to see if prions play any role in demyelinating diseases that stem from the brain,” he says.

“Treatment of CJD targets prion proteins, which are assumed to be doing the damage,” says Mead. “But if CJD did indeed turn out to be caused by absence of prions, then we would have to rethink this therapeutic approach.”

Claude Carnaud, an immunologist working on prions at the INSERM research unit of the Pierre and Marie Curie University – Paris 6, says that some brain disorders that have been considered inflammatory in origin look like they may instead involve an absence of prions in the brain, at least in mice. “It will be very interesting to see if this also applies to multiple sclerosis,” he says.

References

Prions ‘may keep nerves healthy’ | |||

출처 : BBC 00:02 GMT, Monday, 25 January 2010 Swiss researchers say there is evidence that prions play a vital role in the maintenance of the sheath surrounding our nerves. They say it is possible that an absence of prions causes diseases of the peripheral nervous system. One expert said there was growing evidence that the prion had a number of important roles in the body. As well as the latest research in the journal Nature Neuroscience, other studies have indicated prions may protect us from Alzheimer’s disease or even play a role in our sense of smell.

The prion protein only came to the attention of scientists in recent years as they searched for the cause of vCJD – the human variant of BSE, or Mad Cow Disease. This degenerative and incurable brain condition is now thought to be caused by a “mis-folded” version of the prion. However, there is still little understanding of what the protein is supposed to do in its normal, healthy, form. Healthy prions The study, by scientists at the University Hospital in Zurich, looked at mice bred with fewer prion proteins. While these mice are known to be resistant to prion diseases equivalent to vCJD in humans, they showed a number of abnormalities, including a degeneration, later in life, of the peripheral nerve cells, and the protective myelin sheath which surrounds them. Peripheral nerves are those which link the limbs and organs to the central nervous system – the spinal cord and brain. Looking more closely, researchers examined the effects of removing the prion protein in both the nerve cells themselves, and the Schwann cells surrounding them, which are responsible for making the myelin sheath. While removing protein from the Schwann cells had no effect, taking it from the neurons led to a breakdown of the myelin and degeneration of the nerve cells. They said that the knowledge that prion protein played some role in the healthy upkeep of nerve cells could offer a new avenue of research into diseases affecting humans. However, scientists caution that it is too early to pick out a particular peripheral nerve condition which might correspond to the mouse experiments. Recent work Professor Nigel Hooper, from the University of Leeds, agreed that the role of the protein was not well understood. His own work, published in 2007, suggested that it might offer some protection from the development of Alzheimer’s disease. But he said this was unlikely to be the complete answer. He said: “Most people started by focusing on prions in relation to a human disease, and have only recently started to examine what it normally does. “There is some evidence that it could have a number of different roles, depending on its whereabouts in the body – a recent paper linked it to olfaction or the sense of smell.” | |||